|

|

|

|

|

Sugar is a thirsty

crop. It takes one million gallons of water a day to

irrigate 100 acres of sugarcane. (Sugar Water) Modern

sugar planters knew that their success depended on moving water

from the streams to their fields. Once this water left the watershed,

it was never returned. How did the plantations alter traditional

water management practices? |

|

|

Plantation:

Water uses Sugar Water by Carol

Wilcox as a major source for pictures and text. Used with permission

of the author. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Traditionally, the konohiki

allocated the water resource based on individual use and

maintenance. When disputes over water arose, it was the konohiki

who was responsible for their resolution.

(Sugar Water) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Limahuli kalo

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After the mahele, water that had been used for the mutual

benefit of all became water used for private gain. To support

this new industry, the government allowed the sugar plantations

to take as much water as they desired from the streams. This

was in great contrast to the traditional practice of taking

no more than 50% of the stream's flow. Once water is diverted

into tunnels, it is not always possible to restore it to the

watershed where it came from. (Sugar Water) Photo

by D. Franzen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The five streams of Nawiliwili were

all interrupted or diverted by reservoirs and ditches in their

upper reaches by the plantation. Pu'ali Stream was cut off historically

from its natural head waters. Now it is connected to reservoirs

on the east and west sides of Puhi. (Kido) |

|

|

|

| This change in water

use impacted those native planters who depended on a fair share

of the stream resource. New disputes over the water resource

ended up in the water commissions and courts. It is not surprising

that that there was little protest over this change in water

management. Hawaiians had lost their traditional culture, their

population was being wiped out by disease, and their land was

in the hands of foreign businessmen. (Sugar Water) Without

land, the water resource meant nothing. (Damon) |

|

|

|

A diversion like this could easily

handle 50 million gallons a day. Photo by D. Franzen

(Sugar Water) |

|

|

Traditionally, water rights went

with land use. From 1850 to 1973, the commissions and courts

consistently declared that surplus water went with the land,

allowing the plantations the right to divert water to wherever

they chose. (Sugar Water) |

|

| Many water diversions

were so remote that their existence and impact were not recognized.

(Sugar Water) Photo by D. Fleming |

|

|

|

|

|

Lihu'e Plantation built 51 miles of ditches with 18 intakes

from streams. Their system diverted an average of 100 - 140

million gallons a day. (Sugar Water) To the right,

William Harrison Rice built Lihu'e Plantation the first sugar

irrigation ditch in Hawai'i in 1856. |

|

|

|

|

|

George N. Wilcox began building a series of modest ditches for

Grove Farm in 1865. By the 1920's, Grove Farm had 16 miles of

ditches diverting 26 million gallons a day, some of it through

Ha'upu Ridge to Koloa Plantation - out of the watershed. (Sugar

Water) |

|

|

Grove Farm's Lower Ditch

Photo by D. Franzen (Sugar Water)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This flume carries water from Mt. Kahili into a tunnel through

Kilohana - final destination, Lihu'e.

Photo by Adam Asquith. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The same flume, from the inside.

Riding the water in these flumes was once a form of cheap entertainment.

Photo by Adam Asquith. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above, ditches for sugar water.

Map from Sugar Water |

|

|

|

|

|

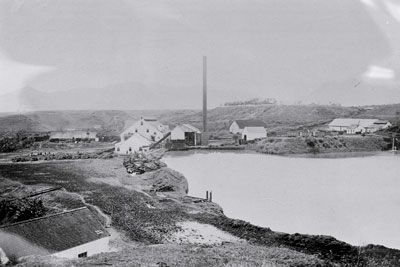

| Another use for water

that Hawaiians never considered was hydropower. Plantations

built dams and used the flow to make electricity, run their

water pumps, and power their mills. To the right, a dam was

built on Nawiliwili Stream to create this pond to run the Lihu'e

Mill. In the 1940's, Grove Farm built a power plant on Papakolea

Stream. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's another angle on the Lihu'e

Mill Pond - courtesy of the Baker Collection, Kaua'i Historical

Society |

|

|

|

How did this new sugar water affect

the sustainability

of the ahupua'a at Nawiliwili Bay? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|